Three tall women discuss acting, memories and the pointlessness of critics.

Three women are having a natter around a restaurant table. Death is on the agenda. Ruth Cracknell, Pamela Rabe and Pippa Williamson are discussing the recent death of Williamson’s cat. The conversation moves to a dying man’s final words, cremation and fear of death. It’s a way for us break the ice.

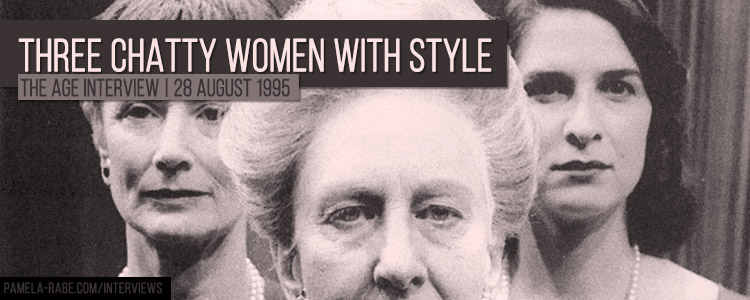

They are all appearing in Edward Albee’s play Three Tall Women. It was typecasting. “I’m the short one. I used to be, and probably still am, five feet eight and three quarters in the old term,” says Ruth. Pippa is: “Five, 10 and a half, though I’m probably shrinking.” Pamela: “Just under six foot. I’m not aware of it until people comment. And when I see photographs of myself.”

Ruth says she wouldn’t be short for quids. Her height didn’t damage her career even in the early days. “It was great for Greek tragedy and Shakespeare. Great for radio.”

“You played the seven dwarves didn’t you, Ruth?” Pamela asks.

“Yes, I played Grumpy.”

The character of the matriach played by Ruth in Three Tall Women is inspired by Albee’s dislike for his adoptive mother. But, much to his surprise, audiences have found her fascinating and even warmed to her.

Are memories of family difficult to communicate to others or were his feelings hard to translate? Pippa says everybody’s stories about their lives are fiction.

“It’s how you frame it. How you see it is not necessarily how somebody else saw it,” Pippa says. “My aunts and uncles have a totally different view of my grandmother than my mother has. Each of them had a subjective view of their mother … When you see it in the context of her life, you see what made her who she became.”

Pamela continues that thought: “And that in itself becomes a form of acceptance on behalf of the writer — that he should even choose to investigate what has gone into making this woman.”

Ruth Cracknell sits back in her chair and answers questions about her close relationship with her mother, plugging a forthcoming autobiography along the way. She speaks very softly and meanders around the point a lot. But there is something compelling about a quiet, well-spoken woman in her 70s with a polite sense of stature.

Pamela, a Melbourne Theatre Company veteran who looks younger than her 36 years, takes less of a role in discussions — checking what we are talking about every now and again. Perth-based Pippa, 54, is probably the least known of the three actors. She has mainly directed for several years. The breeding shows through when Pippa forms shapes with her mouth as she pronounces words.

The conversation continues in a broken fashion about the way we choose to remember, repressed memory syndrome. “They say you can’t remember pain, maybe you can’t remember pleasure either.” Pippa is a theorist.

The three are of incomparable age, but they are all articulate, chatty, carry a similar sense of style, and defer to each other. They’re professional friends. Ruth muses then whispers: “I suppose the thing about performers is you do develop a closeness over a period of time because of the intensity of the business.”

Pippa adds: “It’s the energy. It’s not about biographical data.”

But does it matter if actors don’t get along? Pippa’s cryptic answer is: “The reality of the task at hand is that you enter a different reality.” She’s been doing it all afternoon.

Through the reality discourse we learn that there is a guardian angel in Ruth’s life. “Mine’s reading Middlemarch at the moment.” (Everyone peals with laughter.) The camaraderie is running over. So what happens when one is singled out for harsh criticism as Ruth was in Sydney for her performance in this play? Frowns ensue from Pamela and Pippa as Ruth mildly explains her attitude to theatre criticisms: “I never read reviews so it is of no concern to me:”

So they haven’t discussed it?

“What? Reviews?” they chorus. Now things have hotted up.

The person who perhaps has a right to criticise or comment is one’s director,” Ruth says.

Pippa continues: “Our task is to work on what we create in a space together and we don’t want to be distracted.” Ruth, who claims not to have read a review for eight years, adds: “A fantastic review, in my book, is just as damaging as a lousy one. I mean why would one bother to read them?” Because we all have an ego? “I’ve ggot a huge ego. But what profiteth the man to read the review. There are many people whose opinions I value and if they say something, sure… but not critics.”

But reviews do mean something.

In America, Frank Rich can close plays on a whim and here we have seen playwrights wounded and entrepeneurs damaged.

“Did you ever see Frank Rich on the Albee documentary?” asks Ruth. “You look at them (critics) and you think… I think I’ll shut up. If somethings’s not working I know before anybody.”

We discuss characterisation and learning to cut through the lies of the character – denials and truth. The reading between the lines – insight.

Later Ruth asks me to ask her about how old she feels. “Oh about 18.”

She’s acting.

Words and picture by Chris Beck.

Source: The Age | 28 August 1995